News

Home page online

This web site is a work in progress and being regularly updated. Please check back frequently to view new and updated pages.

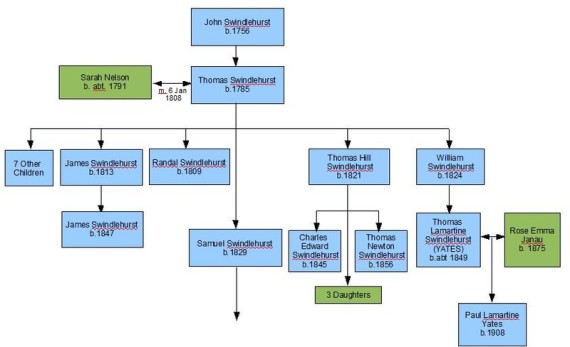

Chapter 5 William Swindlehurst (1824 – c1891) and the Lamartine Yates

William Swindlehurst was mentioned a few pages earlier, when he was just a small boy at one of his Fathers’ temperance speeches. William was Thomas and Sarah’s eighth child and was to become as famous as his father – or rather, in his case, infamous. He was born on 11th December 1824 in Preston.

It is likely that he apprenticed to his father and became qualified as an engineer and worked at his father’s factory for some time. Despite that, his interest appears to have been in property development and improvement of living conditions for the working classes.

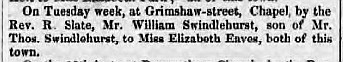

He married Elizabeth Eaves on Tuesday 10th August 1847

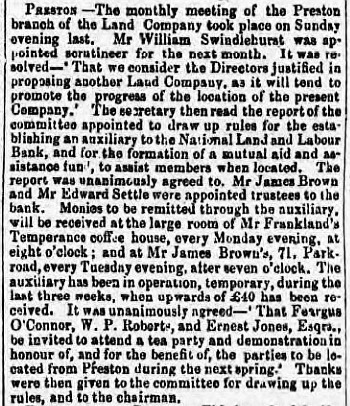

William’s property development work began in Preston when he became involved with the Chartist Land Company as a committee member. The press cutting below from the Northern Star on 12 February 1848 shows his early appointment as “scrutineer” for the company:

The Chartist Land Company was launched in 1845 with the aim of resettling industrial workers from the cities on smallholdings, making them independent of factory employers and potentially qualifying them for the vote. Chartists deposited regular amounts towards an eventual £2 10s share in the venture, deposited in an account held by Feargus O'Connor in the London Joint Stock Bank. By early 1848 more than 70,000 supporters had subscribed.

But the company ran into organisational difficulties when it was refused registration as a friendly society. So the society was renamed first the Chartist Coooperative Land Company and later, the National Land Company as it tried to be registered as a joint stock company. However the task of complying with the legislation proved to be an impossible one and it became clear that the land company was fatally flawed.

Further problems arose when there were allegations that O'Connor had siphoned off money from his newpaper company, The Star, for his own use and was now doing the same with the land company. O'Connor duly denied the accusations and evidence today suggests that O'Connor was innocent of the charges. However, the allegations persisted. Eventually there was a parliamentary inquiry into the land company, and in August 1851 an Act of Parliament wound up the company.

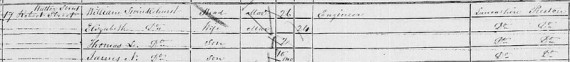

By the 1851 Census, William was living in Manchester, at 17 Robert Street. Scandal and controversy surrounding the companies he was involved in was to follow him later in his life. For now though, it appears that he continued to work as an engineer.

In 1858 he was secretary of the Wandsworth Workingmen’s Co-operative, (Source: Janet McCalman. Respectability and Working-Class Politics in late-Victorian London. Thesis Australian National University (July 1975)), and is shown on the 1861 census living at 6 Tibbert Street, Wandsworth, Surrey, employed as a mechanical engineer.

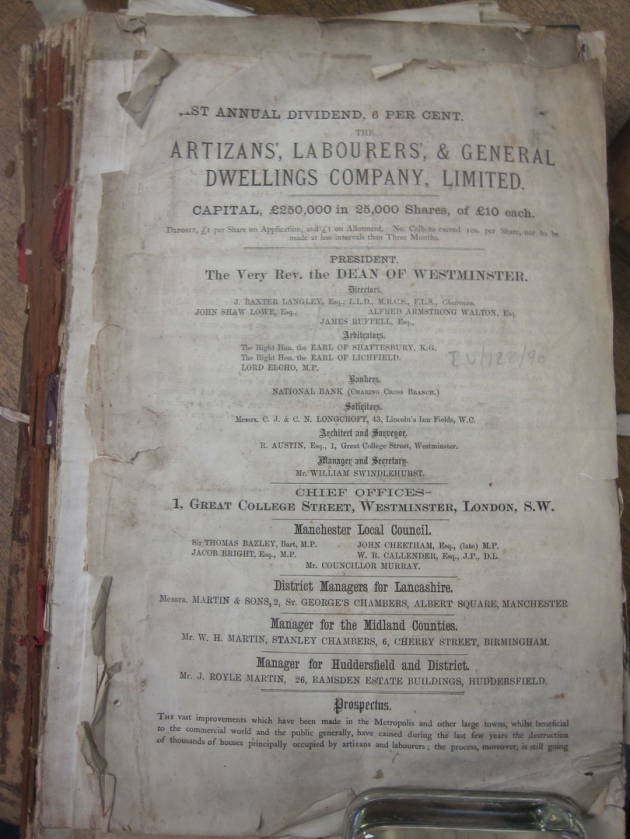

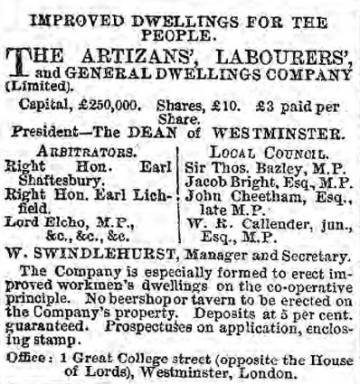

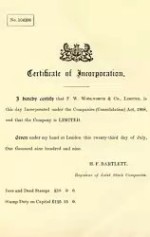

On 8th January 1867, the Artizans', Labourers' and General Dwellings Company Limited (ALGDC) was registered. This was a philanthropic model dwellings company which sought to improve the living conditions of the working classes. Fifty-five shares were subscribed to by seven people, one of whom was William Swindlehurst, who held ten shares. At the time he was living at 41, Guildford Place, Kennington Lane, Surrey, his profession was still as an engineer. William became the manager and first company Secretary “at a salary of not less than £150 a year” (although this was later reported to be £500 a year), and in December 1869 became the permanent Company Secretary.

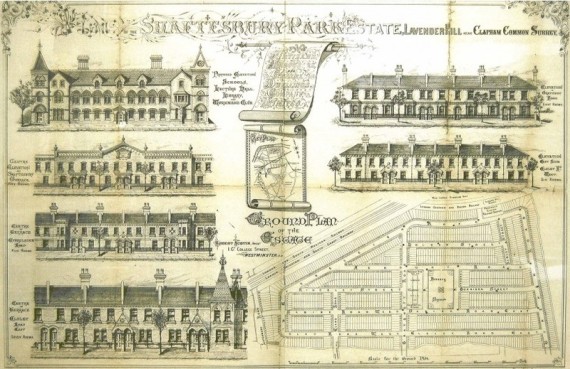

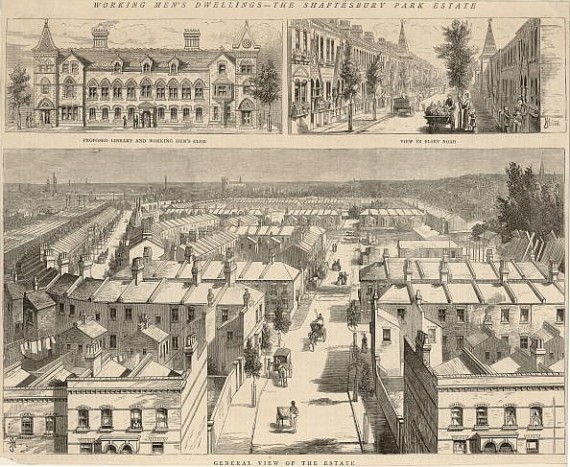

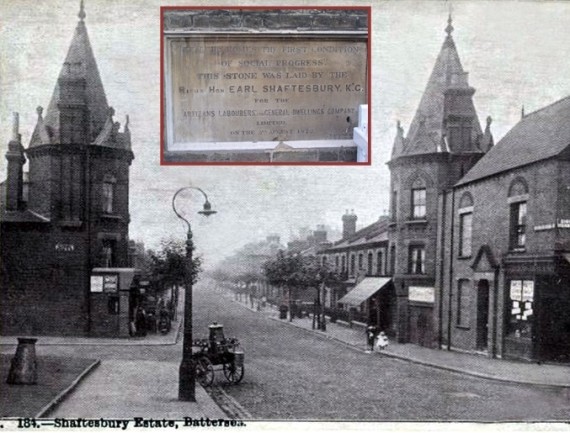

Large estates have been secured near Clapham Junction and the Harrow-road the former, called Shaftesbury-park, is now covered with about 1,150 houses whilst the partially developed Queen's-park Estate, Harrow-road, contains nearly 800 houses. The estates have been laid out with every regard to the latest sanitary improvements. The Shaftesbury-park Estate is readily accessible from Kensington, Victoria, Waterloo, Ludgate-hill, and London-bridge, at low fares; while the Westbourne-park Station on the Metropolitan District and Great Western Railways, and the Kensal-green Station on the Hampstead Junction and North London Railway, and the new station on the London and North-Western main line, with a good service of omnibuses, make the Queen's-park Estate at Harrow-road almost equally accessible. The sale of intoxicating liquor is altogether excluded.

The company reserves the right to prohibit sub-letting, or to limit the number of lodgers. There is a co-operative store on the Shaftesbury-park Estate as well as a

handsome hall for public gatherings and society meetings; and on both estates the School Board for London has provided ample school accommodation. The houses are divided into four classes, according

to accommodation and position. The smallest - the fourth-class - contains five rooms on two floors. A third-class house has an additional bed-room. In the second-class house there is an extra

parlour, making in all seven rooms; while a house of the first-class has eight rooms - a bath-room being the additional accommodation. The present weekly rental, which includes rates and taxes,

except in the case of the first-class houses, is as follows:

an ordinary fourth-class house, 7s. 6d.

third-class, 8s. 6d.

second-class, 10s.

first-class, 10s. and 11s.

The shops, corner houses, those with larger gardens than ordinary, and some other exceptional houses, are subject to special arrangements both as to rental and purchase. The company is also prepared

to sell the houses on lease for 99 years, and on easy terms, subject to a moderate ground-rent; the object being to encourage the personal acquisition of the house by payment of a slightly increased

rental. All applications to rent or purchase houses must be made in the first instance to the sub-managers on the estates, and all letters must contain a stamped envelope for reply."

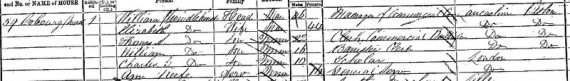

In the 1871 Census, William and his family were living at 59 Cobourg Road, Camberwell, and clearly middle class as they has one servant.

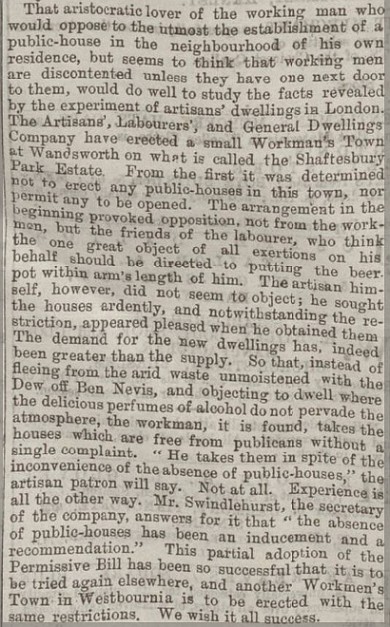

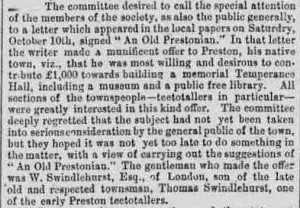

William’s Temperance values were clearly in evidence with the design of the ALGDC estates. As noted above, the sale of any intoxicating liquor on the estate was forbidden. This was clearly revolutionary at the time, as the following article from the Staffordshire Sentinel of 29 June 1874 reveals:

This situation did not go unchallenged and there were several attempts to get licences granted just outside the boundaries of the estate, which were successfully fought off by the Company. As will be seen later, more underhand ways would be attempted by some to get the licenced houses they desired.

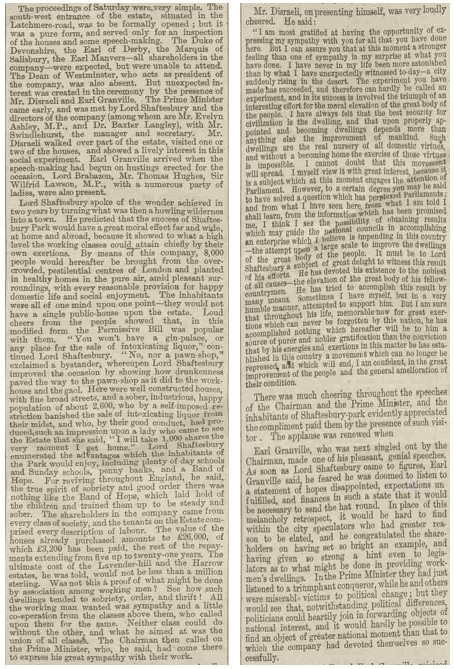

What must have been one of William’s proudest moments happened on July 18th 1874 when a special ceremony took place at the Shaftesbury Park Estate. It involved the official opening of the first part of the estate. What made this particularly significant was the attendance of Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli. The following is an extract of the account in The Tamworth Herald on 25 July 1874 (reprinted from The Times).

By 1874, Thomas and his family were living in a large house known as “Eversleigh House”, Lavender Hill just outside the Shaftesbury Park Estate.

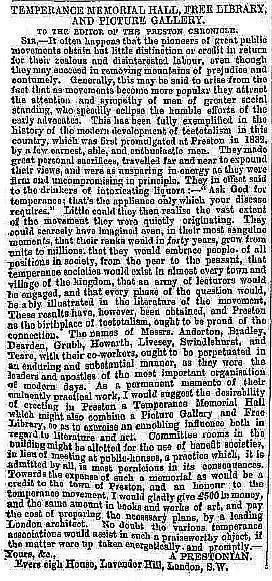

He certainly had a large amount of money at his disposal as his letter (anonymously as “A PRESTONIAN”) to the Preston Chronicle & Lancashire Advertiser, published on 10 October 1874, shows. In it he offers £500 in money and the same amount in books and works of art towards the building of a Temperance Memorial Hall, Free Library and Picture Gallery.

Right: Article from the Preston Chronicle and Lancashire Advertiser from 10 October 1874.

In April of the next year, the same newspaper printed an article on the 24th on the Preston Temperance Society’s procedings and it was noted that this offer had not yet been been considered seriously by the people of the town. Sadly, it was never built, as the money pledged would have been only a tiny amount of the real cost. In 1877, a Preston lawyer called Edmund Robert Harris finally turned, (almost), the same dream of William into a reality. Harris left instructions in his will with a sum of £300,000 to establish a trust that would provide funds to support the creation of several organisations in Preston including a library, museum and art gallery.

Continuing with his philanthropic works, in January 1875 William presented a paper to a National Sanitary Conference in Birmingham on “Hospitals for the Isolation and Treatment of Infectious Diseases.”

The 11 Mach 1875 issue of the London Daily News ran an article mentioning that an application had been made to the Secretary of State for War from William Swindlehurst, manager of the ALGDC for permission to raise a Volunteer rifle battalion in the “Workmen’s City” of Shaftesbury Park. It said that there were already 6000 inhabitants and this would be raised to 8000 when the estate was complete. The application had been made by 400 men who were willing at once to give their services. Authorisation was given by the War Office. The article said that an extensive headquarters with drill ground at the back had already been built and said that with all the men and facilities located on the estate, its proceedings would be watched with interest.

In March 1876 an unusual case of libel by the ALGDC against “Gale and another” was brought before the Lord Chief Justice and a special jury. It related to an article published in the Licenced Victuallers Gazette on 17 July 1875 headed “The Beer-less Estate.” It was made clear in the case the Shaftesbury Estate that there “was not an inn, tavern, public house, beer house or any place for the sale of intoxicating liquor upon the estate.” It would appear that an application was made for a licence to sell intoxicating liquors from a house in the neighbourhood of the estate and a petition was signed by every inhabitant of the estate and presented to the magistrates praying that they would not grant the licence. The licence was refused and shortly afterwards the article appeared. The article was quoted in the London Standard of 15 March 1876:

The Lord Chief Justice (LCJ) asked who had been aggrieved by the article. Mr Serjeant Ballatine replied that it was the management of the estate, but the LCJ said that they could not be responsible if the tenants had done what the article had said and so could not be aggrieved by it, but Mr Ballatine argued that it was an attack on the gentlemen who managed this estate – that in fact they had mismanaged it and the property had deteriorated.

William, as Secretary of the company was called and gave an emphatic denial that there was the slightest truth in the charges contained in the article. He contradicted them on daily observation of the estate, and the manner the tenants of the 1000 houses on the estate conducted themselves.

The LCJ found in favour of the ALGDC and awarded costs of £10 1s.

Much of the day-to-day supervision of the building work of the ALGDC’s Queens Park Estate had been left to William. In 1877 there were rumours of irregularity in the handling of funds and inadequate purchasing procedures, so in June 1877 the company appointed a committee of inquiry. It was found that the board had given Swindlehurst supplies of blank cheques and suspected that he had taken some of the profits from the sale of company land. A particular concern was that building materials had been purchased from a single merchant, Solomon Frankenburg, who had often charged twice the going rate. In July 1877 Swindlehurst and Langley, and later Saffrey, were arrested for fraud, and brought before Bow Street Police Court charged with defrauding more than £30,000 from the company.

Two of William’s brothers travelled to London to put up the sureties for his bail. On arrest these were set at two sureties of £500 each and £1000 personally. At the end of the first hearing, this was increased greatly to two sureties of £1,500 each and himself of £2000 – the two brothers were probably Thomas Hill and Samuel. A summary of the trial is given above and the full account of the case at the Old Bailey is given in the appendices. In broad terms, since 1871, Edward Saffrey, an estate agent, would purchase land on behalf of the company at the lowest possible price. He would then sell this land to the company at a much inflated price. The land for the Queens Park Estate was purchased for £36,000 and sold to the company for £45,312. Saffrey took his cut of the profit and handed the remainder over to be split between Dr James Baxter Langley, William Swindlehurst and John Shaw Lowe. Lowe absconded from his trial.

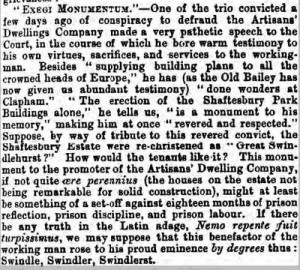

After a four-day trial at the Old Bailey from 23 – 26 October 1877, William was found guilty of conspiracy and, under the Larceny Act, of the misappropriation of the company’s money, the total of which between all defendants came to £24,312. On the day of sentencing, Sir Henry James, on behalf of William, presented a memorial signed by 651 persons connected with the Company in mitigation of his client’s sentencing. As the verdict stood, William could have been sentenced for up to seven years, but the Attorney-General passed judgement only for the conspiracy, for which the maximum penalty was two years, and he was sentenced to eighteen months in prison. It was stated that the sentence would include hard labour.

William was given the opportunity to say a few words at the end of the sentencing. He pleaded to be leniently dealt with, and declared before heaven that what he did was done innocently. His further words were recorded by the Dundee Courier of 27 October 1877:

“William Swindlehurst then spoke with great emotion, alluding to the unimpeachable character he had formerly enjoyed, his efforts on behalf of the working man, and his faithful services in his position of manager to the Company. He had brought long experience to bear upon the discharge of his duties, and he pictured in vivid terms the results of the sentence in the case of a man of his years and former reputation.”

The Leeds Mercury of the same day also covered William’s plea and wrote the following:

“The defendant Swindlehurst also begged to be allowed to say a few words in mitigation, and he said that for fifty years he had devoted his whole mind and attention to improving the condition of the working classes, and providing proper accommodation for them. He said he was the projector of this company, the object of which was to provide healthy and proper accommodation for the working classes, and which he started under great difficulties, and he had only received a salary of £40 a year during the ten years the company had been in existence. An arrangement was made that he should be paid 5 per cent on the amount of the share capital, and he considered the company owed him £15,000 at the present moment. He asked for mercy on account of those facts, and the serious blow that had been inflicted upon his family by these proceedings.”

The North Devon Journal of 28 March 1878 stated that “When Dr Langley and Mr Swindlehurst were found guilty, the judge told them that they would at the end of their term of punishment be liable to be brought up again on the other and graver counts of the indictment, and that the course to be adopted would depend in great measure upon the steps which they took meanwhile to restore to the shareholders the amount of which they had robbed them. Mr Swindlehurst has surrendered property to the value of £3,200.”

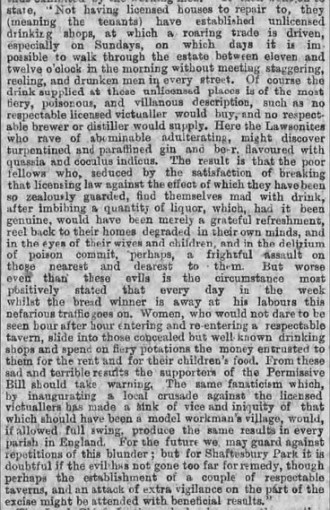

The newspapers did not have much sympathy with William and thought the sentence was too lenient. No doubt the moral turpitude of the offences was greatly enhanced when set against his life-long devotion to practical philanthropy, much like the abhorrence of someone stealing from a charity. They were also scathing in criticism of his pleas for mercy.

The York Herald of the 27 October said that the “general feeling is that Messrs Baxter Langley and Swindlehurst have escaped very lightly … They did not improve their position, either in the eyes of the court or the public, by the canting speeches which they made this morning from the dock, and which were delivered with a great deal of oratorical flourish.”

The Worcestershire Chronicle of 10 November 1877 ran the following article (right) and the name Swindlehurst, was being viewed as a dirty word, with the emphasis on the “swindle”. It can only be imagined how 21st century media would have treated the name in their headlines.

In Reynold’s Newspaper of 18 November 1877, it said that all three of the prisoners were undergoing medical treatment and William was “getting more reconciled to the situation” and gives some insight into how difficult prison life was for William.

Despite the machinations of the press, William and the others convicted in this trial do appear to have had a lot of support from members of the public who thought that a great injustice had been done to the men. This was not because of their deeds, but because what they had done was just commonplace in businesses at the time, they were being made scapegoats and honestly believed that they were only receiving gifts from a man who had made a profit on a transaction and that their acts were not illegal, although they must have been aware that it was morally questionable at the very least. A petition was served on the Home Secretary for their release. This was first reported in the Liverpool Mercury on 4 September 1878 and said, “A memorial has recently been laid before the Home Secretary praying for a remission of the remaining portion of the sentence on Mr William Swindlehurst, late secretary of the Artisans’, Labourers’ and General Dwellings Company, and an answer has been received from Mr Cross declining to interfere in the matter.

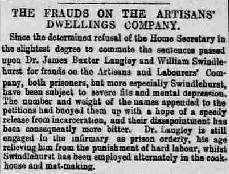

The Western Daily Press of 15 October 1878 had the following article (left) about a second petition, and again mentions the effect prison was having on William’s health.

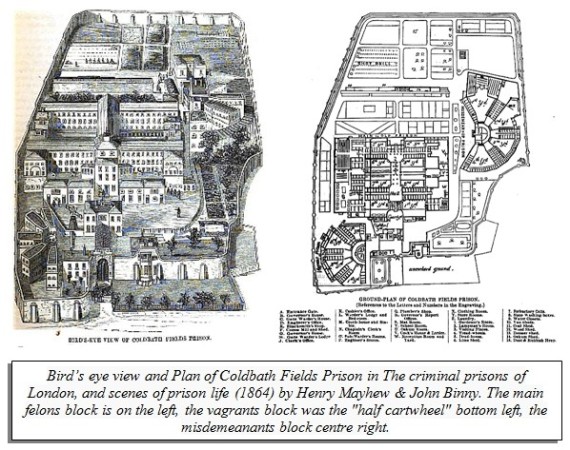

The Leeds Times of 19 April 1879, just prior to his release, said that William was confined in Coldbath Fields Prison, in Clerkenwell, London, and was “employed in darning socks and mending the shirts of prisoners.”

When William was released from prison, he published a pamphlet setting out his own case as a sort of self justification. You can see it here by clicking on "William's Pamphlet" in the index..

William was married and had four adult sons at the time of his imprisonment. His eldest was Thomas Lamartine Swindlehurst. Thomas started his career as an engineer, but must have started studying law in about 1866. At the time of his father’s conviction, he had just qualified as a Solicitor. The trial received much publicity locally in Battersea where the family lived, as well as nationally and internationally. It was a huge scandal and these events must have been professionally and personally embarrassing for him.

It appears that the whole family, (except perhaps James Nelson Swindlehurst), changed their surname to Yates (the significance of this name is yet to be discovered – it was not his mother’s maiden name as one might expect). It is not certain if all changed their names by deed poll as, in later years some reverted to the Swindlehurst name. Thomas decided to use his middle name also as a surname and the change was made official by deed poll in 1878 when he became known as Tom Lamartine Yates.

The Luton Times and Advertiser of 25January 1878 stated that “Eversleigh House, Lavender Hill, the late residence of Mr Swindlehurst, is to be converted into a working men’s institute”. The book “All about Battersea” by Henry S Simmonds (1882) confirms that this happened. It says “The Shaftesbury Club and Institute, Eversleigh House, Lavender Hill, was opened on Saturday, Feb. 2nd, 1878, at 3 o'clock p.m.” This would have been additionally baulking for William as his former home was now being used for drinking alcohol, which went against his temperance principles. It is still thought to be The Shaftesbury Club today.

In the 1881 census Tom is shown as living with his brother William and family at 203 Clapham Road, Lambeth. A few months afterwards he married Fanny Roberts, daughter of a bookseller from Chester. The 1891 census shows Tom and Fanny living at 3 Church Road, Lambeth, a substantial house built in c1825, where they employed one servant.

Their marriage was childless and Fanny died on 13 October 1896, and was buried at Hampton. Tom placed this “In Memoriam” advert in the London Standard, one year later.

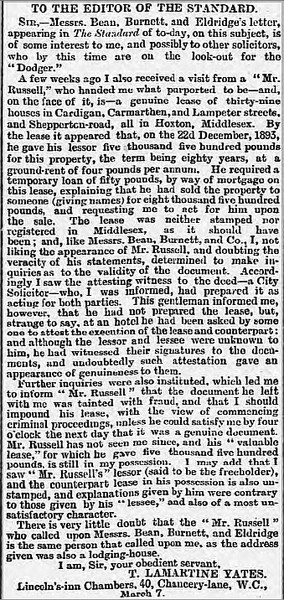

A letter written by Thomas to the London Standard from his Chancery Lane premises and published in the 8 March 1894 edition. The letter tells of a "Dodger" who came to his office to try to pass over some fraudulant paperwork for property.

A letter written by Thomas to the London Standard from his Chancery Lane premises and published in the 8 March 1894 edition. The letter tells of a "Dodger" who came to his office to try to pass over some fraudulant paperwork for property.

Tom’s legal practice, at first in Essex Street off The Strand, was established in 1887 at 40 Chancery Lane, where it remained as Lamartine Yates & Morgan until it was bombed out in 1940. It subsequently continued in Carey Street as Lamartine Yates & Lacey.

In 1900, at the age of 51, Tom married his second wife, Rose Emma Janau, who was 26 years his junior. Rose’s parents, Elphege and Pauline, were French and both had come to Britain independently in about 1867, where they met. They also met Tom, (then Swindlehurst), around this time, so he had been a friend for many years and known Rose all her life. It appears that their courtship began in 1898 and had the full approval of Rose’s parents. Their wedding took place in Stoke d’Abernon in Surrey.

Tom, a keen cyclist, was already a member of the Cyclists Touring Club (CTC) when Rose joined in 1900. After marriage Rose studied law with Tom in order to be able to help him in his practice. During this training, Rose learned with disgust of the inequity in law between the positions of men and women. “The reason such a state of affairs exists” she wrote, “is that by order of man woman is dumb with regard to all the legislative and national affairs”. She already had personal experience of this, having passed the Oxford Final Honours Exam in modern languages and philology in 1899, as a woman she was not allowed to be awarded a degree.

Tom was in sympathy with Rose's ideas and supported her in all her activities and valued her as an equal.

The couple lived in a flat in Torrington Square WC1, before moving by 1902 to Slade Lodge at Fulwell (now Fulwell Golf Clubhouse), which is close to where Tom's first wife is buried. In 1906 they left Slade Lodge and leased a house that they must have cycled past many times on outings from London along the Portsmouth Road, Dorset Hall at 152 Kingston Road. The house had more than 20 rooms and stood in two acres of grounds.

Rose Lamartine Yates with a Votes for Women ribbon pinned to her dress, taken by Col Linley Blathwayt of Eagle House, 1909

Rose Lamartine Yates with a Votes for Women ribbon pinned to her dress, taken by Col Linley Blathwayt of Eagle House, 1909

Rose developed into a woman of fiery and independent spirit. In 1907, whilst pregnant, Rose stood for election and succeeded in winning the seat for the Wimbledon District of the CTC. This was a milestone as previous attempts to elect a woman to the Council had met with failure. Despite her campaigning for women’s rights, Rose publicly stated during here election campaign that she was not a Suffragette. But a year later, in the script of a speech entitled “How I became a Suffragist” she wrote “… on looking into the matter seriously I find I have never been anything else … and … I came to realise that I was and must remain one at whatever personal cost.”

Their only child, Paul, was born on 19th June 1908, the day after his father’s 60th birthday.

On 13 January 1909, the Wimbledon Committee of the Wimbledon Committee of the Women's Social & Political Union (WSPU) became the Wimbledon WSPU (WWSPU) and Rose joined the committee.

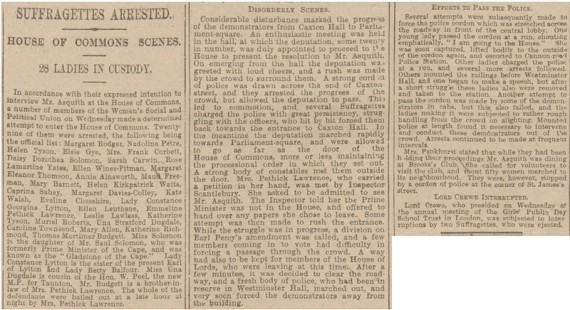

On 24 February 1909 Rose joined a deputation of women, led by Emmeline Pethick Lawrence, from Caxton Hall to Westminster. Their object was to protest to the Prime Minister, Mr Asquith, about the omission of Women's Suffrage from the King's Speech. But the police were waiting for them; the women were punched, tripped, half strangled, picked up and flung down again and again. They were then herded into Cannon Row police station and charged with "obstructing the police in the excecution of their duty".

On the eve of the deputation, Tom had given Rose a letter which read:

"My Dearest,

To day is thy birthday, and what a momentous one.

The present I give thee is not gold nor silver, but the permission freely and gladly to offer up thy liberty for the benefit of the downtrodden woman. To day is the decision - tomorrow the sacrifice whence can only come good tho' it mean pain and suffering to thee.

Years hence, our Paul - our boy - will be proud of his mother and her achievement.

Be not afraid for strength and courage will come to thee in the hour of need.

Tom"

At her trial, with Tom in court as her solicitor, Rose made her famous speech:

" ... I hope you will not inflict upon me, in addition to the indignity of standing in a common police court, that of asking me to be bound over to keep the peace, thereby suggesting that I am a coward, and not a woman at all ... I have a little son who is only eight months old, and his father and I decided ... that when the boy grows up he might ask me, 'What did you do, mother, in the days of the women's agitation, to lay the views of the women before the Prime Minister?' and I could not blush if I said to him, 'I made no attempt to go to the Prime Minister.'"

Rose was imprisoned for one month. A fellow prisoner, Lady Constance Lytton, in her book "Prisons and Prisoners" described the journey to Holloway prison in the horse drawn black maria.:

"We started singing the Women's Marseillaise and another of our songs. Those in the passage managed to put a scarf with our coloursthrough the ventillator under the coachman's feet." In Rose's own copy of the book she pencilled "This was done by Rose Lamartine Yates. They never discovered how they [the colours] waved under the coachman's feet."

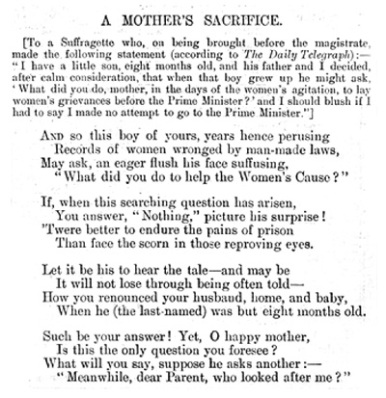

In Punch Magazine on 10th March, Rose was rebuked in verse for abandoning her home, husband and baby, and implicitly, her proper duties as a woman.

On 24th March Rose and her 25 collegues were released. Later they were all awarded with he "Holloway Brooch", designed by Sylvia Pankhurst.

On her release Rose continued as an active member of the Wimbledon WSPU. In 1910 she became treasurer and organising secretary for the branch. She regularly chaired meetings on Wimbledon Common and, when the Government tried to prevent the WSPU from holding public meetings in open spaces, Rose maintained the right of free speech on the Common, despite facing hostile crowds held back by a large police presence.

Rose Lamartine Yates planting a tree with Annie Kenney looking on, taken by Col Linley Blathwayt of Eagle House, 1909

Rose Lamartine Yates planting a tree with Annie Kenney looking on, taken by Col Linley Blathwayt of Eagle House, 1909

In October 1909, Rose made a brief lecture tour to Monmouth and Bath. It is likely that her base was Eagle House in Batheaston, where Colonel Linley Blathwayt and his family regularly gave hospitality to Suffragettes. More than 60 suffragettes came to stay with the Blathwayt family after they were imprisoned for their political activism. The colonel was an amateur botanist and during their stay, the women were encouraged to plant trees and bushes as a symbol of their hopes for political equality.

Each tree planted by a Suffragette was marked by a plaque. He photographed the planting ceremonies, including Rose planting an Austrian Pine on 30 October 1909. The arboretum was destroyed in the 1960s to make way for a housing estate, and only one of the trees survives - the one planted by Rose.

Tom was a member of the Men's Political Union for Women's Franchisement and often acted as solicitor and legal advisor for WSPU prisoners. He also got involved in demonstrations and on one occasion he was arrested along with three women of the WWSPU at a mass demonstration at the House of Commons in November 1910. This was to have major repercussions for Tom as it affected his business for years afterwards. He did however represent the family of Emily Wilding Davison, (who famously fell under the King's horse at the 1913 Derby), at her inquest.

In 1918 Rose was elected as the only Independent member of the London County Council where she was instrumental in incorporating Britain's first cycle lane in St. Helier Avenue, Morden. She was also a Governor of the London Academy of Music and she founded a children's clinic in Waterloo.

Paul was an exceptionally bright child and he was soon performing at fund-raising events and was encouraged to garden and cook - he won a prize for "a meal for a working woman for 10d". Until he went to prep school at about eight, his long fair hair was allowed to grow unchecked and he was dressed in the loose smocks and tunics often worn then by children of either sex. This can be seen in the pictures above.

From 1920 - 6 Paul attended Sidcott School in the Mendips, which was co-educational and run by the Quakers. Here in 1924 he passed School Certificate with honours.with distinctions in music and geography.

In the autumn of 1924 Tom, Rose and Paul spent about three months in Africa, in particular visiting a plantation with orange orchards, 80 miles from Pietersburg, where Tom an Rose considered settling. While they were there, Paul completed a symphonic composition for 13 instruments. They continued their travels from the Cape into Rhodesia, by train and car, spending some nights camping in lion country.

Paul took a double first in history and economics at St John's College , Cambridge, and then went to Germany to study music under Hindermith on a scholarship before finally deciding on agricultural economics as a career.

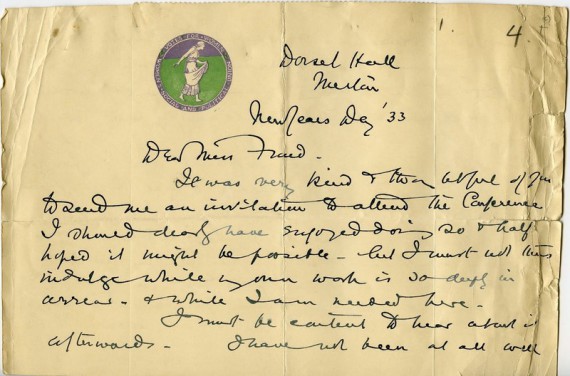

Tom died in 1929, after which Rose started collecting suffragette memorabilia, which now forms part of the collections of the Women's Library.

During the second world war Paul married Ruth Hume, with whom he had four children. Paul was then working for the government, and eventually for the Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations. After the war he took a post as an Agricultural Controller for the colonies.

Rose died in 1954.

After working for the Commonwealth Development Corporation Paul was head of the European Section of the Food and Agricultural Organisation for many years and was based in Geneva. He was there until he was 65 and then continued working for an additional ten years as an agricultural economics advisor in Mexico.

From the age of 95 to 97, he was busy writing a very large autobiography dealing with every aspect of his life and work. It has not, as yet, found a publisher. He was living in France with his 3rd wife on his 100th birthday. Paul died on the eve of his 101st birthday on 18th June 2009.