News

Home page online

This web site is a work in progress and being regularly updated. Please check back frequently to view new and updated pages.

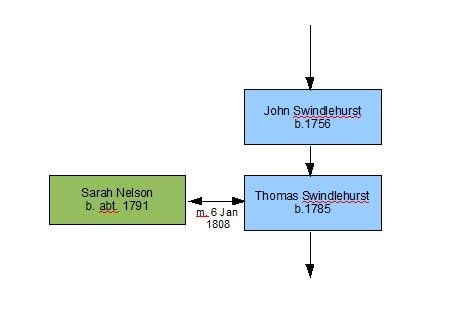

Chapter 3 Thomas Swindlehurst

(1785 – 1861)

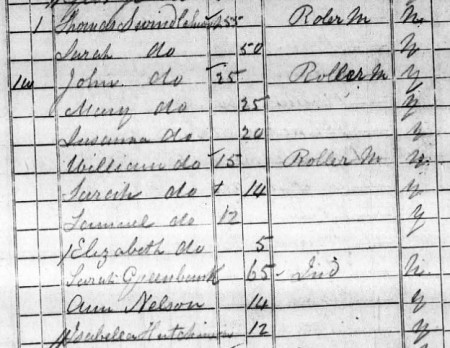

Thomas and his twin sister Mary were the 4th and 5th born children of John and Ann and were born on 29th January 1785 at Slaidburn in Yorkshire. Both were christened on the 13th February, but Mary died 5 days after this.

An insight into the tough start Thomas had in life comes from a newspaper in February 1835 where, at a public meeting called to press the Government for a Ten Hours Factory Bill to be passed, he described his early working life on night shifts at a mill when only six years old:

The article reported that ‘His father was a blacksmith in the Forest of Bowland with six children who being unable to maintain them by his own exertions was obliged to send him and his two little brothers to a factory when he was only six years old. He had for six years worked night work from seven at night till six in the morning. When he left the mill he went home and got what he called his supper at six o’clock in the morning. But as little lads did not like to sleep in the daytime, in place of going to bed to recruit his strength, he used to stroll in the fields and play till the afternoon, when he became overpowered by sleep.’

Thomas’ father was never fond of the factory and his mother was so much against his sisters going that she said she would work her finger ends off before they should go to it. His sisters were younger than he and his brothers and they worked at the factory to maintain them and keep them out of the factory.

But at the end of six years, his father was determined to take them away from the factory and from where they were then living (possibly Halifax). He set off back to Bowland and found that the smithy that he used rent was available again. He decided to take it on and struggle through and that’s where his mother brought up his sisters to “wash and sew and make and mend, so that they might make their own shifts and their husband’s shirts and be good housewives”

Thomas married Sarah Nelson on 6th January 1808 in St Peter’s Church, Bolton-le-Moors, but must have moved to Preston soon after as it appears that their first children were born in the town.

In all, they had 12 children although two died. Sarah (b 1823) died in her first year and Napoleon Joseph (b 1833) died at the age of 10.

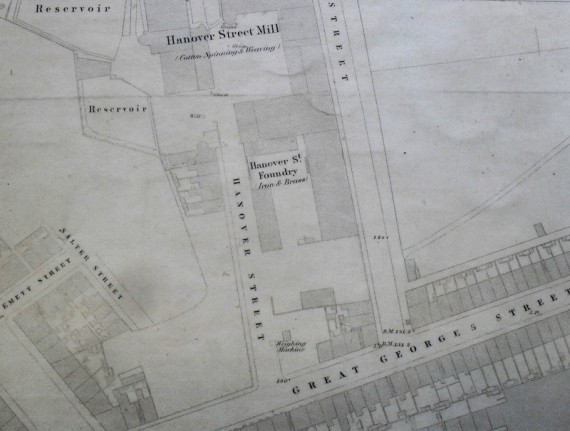

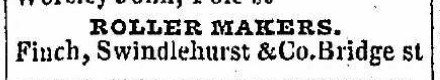

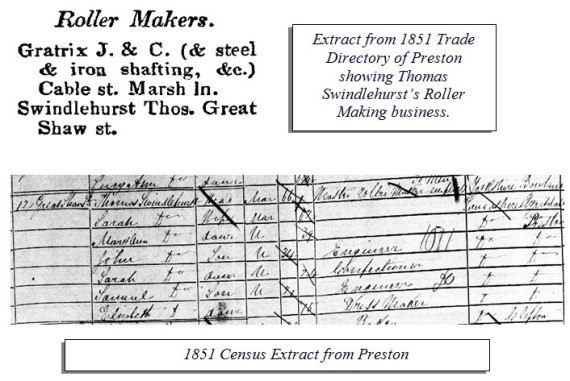

Thomas apprenticed to Mr Frank Sleddon, a Preston machinist, and started his own business in around 1815 as a Roller maker for the cotton mills, later describing himself as a Master Roller maker. By the standards of the time, he had a very high income from his business, and amassed a moderate fortune by earning £4 or £5 a week. (The average earning for an adult mill worker was around 18 shillings). It is not known what year he entered into a partnership with Thomas Ireland but there is an entry in Baines’ Directory for 1825 for the company, which interestingly is written as “Ireland and Swinglehurst” and was located in Hannover Street.

The partnership was disolved in 1827, as reported in the Western Times on 27th October of that year. By 1830 his business was operating from Bridge Street (now Marsh Lane), off Friargate, Preston.

Thomas was a Methodist. Some of his children were christened in methodist churches and some in Church of England Churches, although this was common with Methodists at the time.

Unfortunately though, he became a notorious drunkard and a backslider from religion and as a result, not only did his income fall, but also what he did earn was spent on drink and he was sinking into ruin. In 1830 Messrs. Mather, Roscoe & Finch, iron merchants of Liverpool, sold iron to Thomas’ company for the sum of £110 (around £11,000 in today’s value) which he did not pay for. In the autumn of that year John Finch was sent to Preston to see him and try to get their money. After a long search he found him in the Sun Hotel public house, Friargate, where he was “tolerably sober”. In the conversation, recorded in the “Ancient and Modern History of Teetotalism”, Thomas told Finch that he could not pay him at present but said that no man would lose a farthing by him. He promised that he would pay in full (“twenty shillings in the pound”) if his creditors would have a little patience with him. But Finch said candidly to him that he had no hope he would ever be able to pay it while he continued his present course of conduct, referring to his drunkenness.

It was from this point that Finch took Thomas in hand and began to reason with him in order to change his ways. He asked him how many children he had and Thomas replied that he had a large family of nine children and that he loved them and would lay down his life for them. Finch asked if he thought it would be right to abandon “a worse than beastly habit for them.” He said that soon Thomas’ children would be trying to get a job but would be refused employment when the employer found out that their father was “one of the most drunken men in town”. He said they would be in despair and could even fall into the same vice as their father and would ruin and destroy themselves. Thomas said that he knew he had done wrong and was doing wrong to his family continuously and it made him miserable to think about it, but he had got himself caught in a downward spiral and owed money to a number of people. Whenever he went back to his workshop to work, he had his creditors calling on him, teasing and threatening him. So, to get away from it he would go to the public house or even across the fields, “as wretched as a man can be.” Drink had completely demoralised him; his health ruined, his character lost, his hopes blighted and family hungered. “Under these painful circumstances,” said Thomas, “I was often tempted to put an end to my existance, though I always put on a smiling countenance with my pot companions”

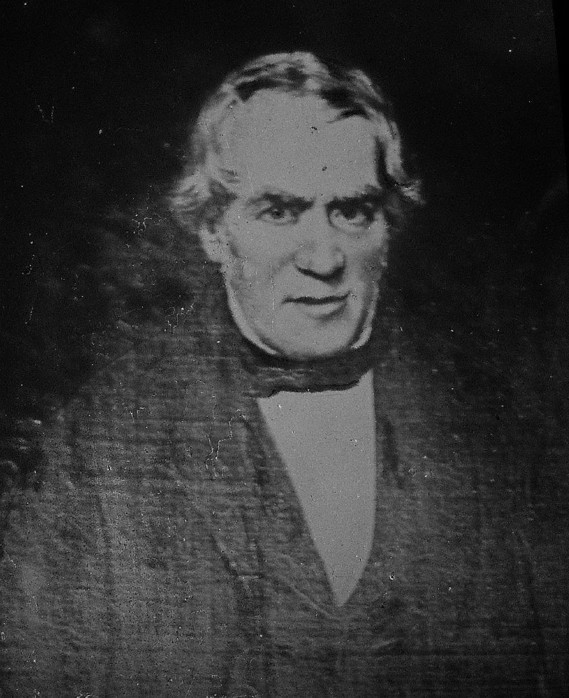

Thomas’ appearance in this painting is very different to drawings and photographs in later years. Obviously he is younger in the painting, fatter-faced and has been spruced up for the painting – he was known for having a ragged, unkempt appearance. Also, there would have been some artistic licence applied.

Finch told him that there was a remedy and said that he had a Temperance Society in Liverpool where men sign a pledge to abstain completely from spirits and to take wine, ale and other drinks in moderation. He said that it would cost him no money, but he had to sign a pledge and keep it. He said to Thomas, “You will easy get through your difficulties when you are a sober man.” Thomas agreed immediately and signed his barely readable name, steadying his trembling right hand with his left. Thomas then gave Finch access to his accounts so that he could evaluate his state of affairs. Finch concluded that if he became sober, attended to his business and paid his creditors, there would still be surplus money, but if he sold up, he would barely have enough to pay his creditors half of what he owed them.

He said that Thomas should go to his creditors and tell them of his pledge, and ask that they gave him some time to repay them. Thomas promised he would do this and as Finch left, he told him that no man had ever talked to him in that way before.

Thomas did as he had promised, but his creditors had no confidence in his reform, were clamorous and would not wait at all, so he wrote to Finch and told him of this. Finch went to his partners to see if they would help Thomas out of his difficulties and this resulted in him traveling to Preston in April 1831 with their terms. They agreed, in addition to their own debt, to advance Thomas iron and money to the value of £350 so that he could pay off his other debtors. This was a huge amount of money, (Thomas now owed the modern equivalent of about £46,000 to the firm), and this demonstrated the faith and confidence Finch had in Thomas.

Finch forwarded a number of Temperance tracts to Thomas, setting forth the ravages of strong drink, and Thomas distributed these, which became the subject of town gossip. He also enlisted the help of John Smith (a tallow chandler), who afterwards also became a devoted temperance worker. These leaflets eventually came to the attention of Joseph Livesey.

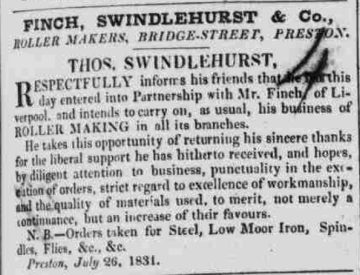

Finch’s faith in Thomas was demonstrated further a few months later, in June 1831, when Finch dissolved the partnership with Messrs Mather and Roscoe and “finding Swindlehurst an honest and upright man, he proposed joining him in the roller-making business.” He did so on July 26th 1831 and, as announced in the Preston Chronicle of July 30th of that year, the company of Finch, Swindlehurst & Co was formed.

His faith paid off as the new business partnership of Messrs Finch and Swindlehurst, in Finch’s own words: “increased that money tenfold; whilst Swindlehurst, by retracing his steps and becoming a sober man, has been relieved of all his debts and difficulties, acquired some hundred pounds, is highly respected, a comfort to his family, an ornament to society, the pride of Preston, and a blessing to the world.”

Thomas’ conversion to temperance was not as straightforward as Finch’s account implies as Thomas tried to follow Finch’s regime of moderate drinking

As recorded by Finch in the Liverpool Albion magazine in 1836, Thomas told him on one of his visits, “This moderation pledge of yours, Mr. Finch, is nothing but sheer humbug, botheration and nonsense, for I find that, after I have had one glass of ale, I have a greater desire for the second than I had for the first, for the third than I had for the second, for the fourth than I had for the third, etc.; and though I have drunk no spirits since I signed the pledge nor more ale on an average than your moderation allowance of three glasses a day; still, as I am fond of company and the pledge does not prevent me from going to public-houses and giving drink to others, I have schemed to get drunk on several occasions. Sometimes I have taken all my allowance together in the evening or at one sitting; at other times one or two glasses, or none at all for several days, and then I had eight, ten or twelve glasses due, this made me a good fuddle.” He also said that he could now get drunk on less ale than he did when he was constantly taking it. Finding that he was getting back into his old ways he made a resolution that “I would never take more than 3 glasses in any one day”. On this occasion, Finch was accompanied by his son, John Finch Junior who made Thomas a promise that if he kept to his latest pledge for six months he would give him a twenty shilling new hat, but he would have to forfeit one of the same value if he broke it.

In the autumn of 1832 John Finch again went over to Preston to see how his business partner and “convert” was going on, and he then discovered that Thomas was a total abstainer from all intoxicating liquors, having found it impossible to drink ale and wine in moderation and keep sober. This happened when, one day, while sitting drinking in The Plough Inn on Friargate, he found himself ordering a fourth drink. He held it in his hand and began to talk to it – “Pretty sparkling thing, may I taste thee? Then I am undone forever, for this is my last chance for reform! I will not – cheat, deceiver, liar, thief. Devil thou art, I will not taste thee again for twelve months.” He thought about the twenty shilling hat that Finch Jnr had promised him and he ran home and knelt down and prayed to God for strength to help him keep his resolution, which he had managed to keep up right up to Finchs’ meeting with him. Thomas said, “I shall keep it as long as I live, for I am quite sure, from my own experience that nothing short of total abstinence from all intoxicating drinks can either reform drunkards, or prevent moderate drinkers from becoming drunkards.” Thomas became a total abstainer on Shrove Tuesday, (6 March), 1832. Finch agreed that he would also abstain totally and would take the message back with him to his Liverpool society. It could therefore be said that Thomas Swindlehurst was surely the first recorded person to say that an alcoholic cannot drink in moderation, but must abstain totally from it if they are not to fall back into drink dependence.

It is interesting to note that Thomas described how his health suffered initially when he cut out alcohol completely, what we would now describe as “withdrawal symptoms” from going “cold turkey”. For Thomas, one side of his body became paralysed and he had barely any use in it. His hand shook so that he could scarcely write his own name, and with great difficulty he could only walk a mile. But within three months of total abstinence his limbs were completely restored and he was able to walk ten miles with ease. He said that he felt ten years younger than he had four years earlier.

Thomas administered the pledge of total abstinence in St Peter’s Schoolroom in October 1832 and on April 2nd 1833 signed the Total Abstinence pledge of the Preston Society, although he was already publically advocating the total abstinance from fermented as well as distilled liqour at a meeting in Lawson Street Chapel on April 27th 1832. George Toulmin, editor of the Preston Guardian, said:

“After this, the most earnest friends of the cause began to advocate a discontinuance of the use of all intoxicating drinks, which ultimately led to the adoption of total abstinence.”

(Quoted in Pearce: The Life and Teachings of Joseph Livesey comprising his autobiography with an introductory review of his labours as reformer and teacher, 1885, p. lxxiv).

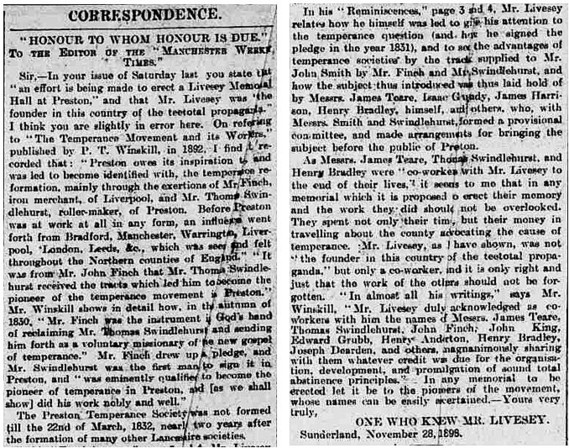

When historians mention the foundation of the Temperance Movement and Teetotalism in Preston, it is only Livesey who is given credit. Livesey certainly had the finances and the literary skills to promote the movement, but he himself never took credit for its original foundation. The following letter to the Manchester Weekly Times, December 2 1898, clearly shows that Thomas was the first person in Preston to sign the Temperance pledge and he became the pioneer of the movement in the town:

In October - November 1833 new premises were being constructed for Finch, Swindlehurst & Co. and this was recorded in the Preston Chronicle of 2 November. A week earlier, a Temperance Supper had been arranged at the Temperance Hotel for 30 – 40 of the workmen engaged at the new building following the completion of the laying of the first floor. The arrangement made with the workmen “was that they should be allowed no intoxicating liquor, but a good temperance supper at the putting on of each floor, The evening was spent delivering appropriate addresses, and in singing several appropriate songs, and was conducted with great order and hilarity.”

It is possible that the new premises referred to was located near the canal side at the bottom of Edward Street. On Tuesday 7th January 1834 at 10am a ferocious wind storm blew across the region causing serious damage to a large number of properties, including the one of Messrs Finch and Swindlehurst. The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser of 11th January reported that, “The chimney of a new factory on the course of erection for Mr Swindlehurst, on the canal side, and a large portion of one of the side walls of the building came to the ground. The premises were of course greatly injured by the fall, but no lives were lost.”

The improving financial position of Thomas was mentioned in the Bradford Observer of 16 March 1837 where it said, “When first he [Thomas] became a teetotaller he owed his doctor £3 18s and 3d. He got this paid off very quickly and since then has not owed him a farthing.” In the same article Thomas says that he employed 50 men, 28 of whom were teetotallers and the rest were sober men. By 1844, in a speech at the annual conference of the Midland Counties Temperance Societies, Thomas said that “he had two large establishments in which he employed about one hundred hands” – The Leicester Chronicle, 1st June 1844.

Thomas went on to become one of the Temperance Movement’s greatest advocates, travelling many thousands of miles in Britain, distributing leaflets and giving speeches on the evils of alcohol and how only total abstinence, or “Teetotalism” was the only way to reform.

He was described as “rough and rude, [his] speech as ragged as [his] clothes, thus, an easy target for ridicule from the non-temperance public”, and was said to be a large, but well proportioned man weighing sixteen stones (102kg). He had a voice of great power and it was often said that he had lungs like “a pair of barn doors”.

For almost thirty years he laboured assiduously, or as Mr. Livesey remarked, "did more than he ought to have done to do justice to himself and family”.

The first of his missionary tours began on 8th July 1833 where he, together with his son Randal, Joseph Livesey and others embarked on a tour through Lancashire and distributed 6,000 tracts proclaiming the principles of Teetotalism. (See article - The First Crusade - in Contents).

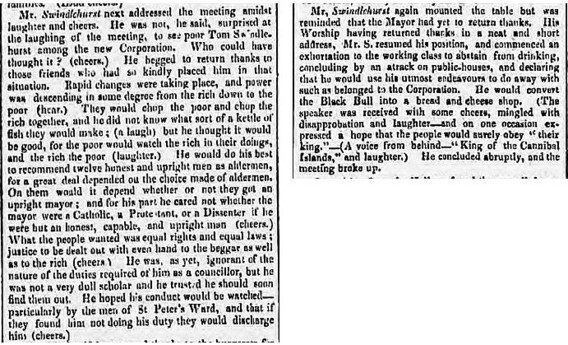

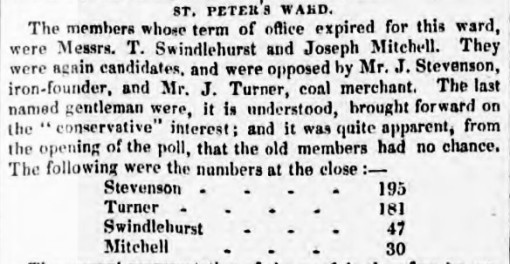

The Corporation Reform Act received royal assent on 29th Sept 1835 which allowed Preston to elect 12 Aldermen and 36 Councillors. Thomas was at the head of the poll and was elected as one of the first Councillors, for St Peter's Ward on 26 Dec 1835 to serve for 3 years. The result: Swindlehurst (131), Mitchell (130), W. Taylor (128), Pomfret (121), Carter (120), German (117).

Thomas’ acceptance speeches) for his election are shown below:

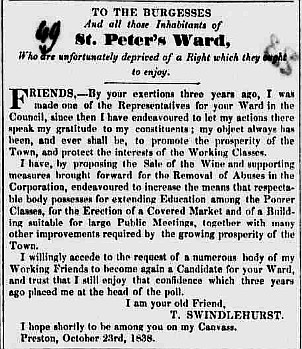

Thomas attempted to run for a second term, in 1838, as this advertisement, placed in The Preston Chronicle of 27th October, shows.

However he failed to be re-elected and he was hugely defeated. The result is shown below.

Thomas did, however, continue a keen interest in public service and was elected as a member of the Board of Guardians (who administered the Workhouses).

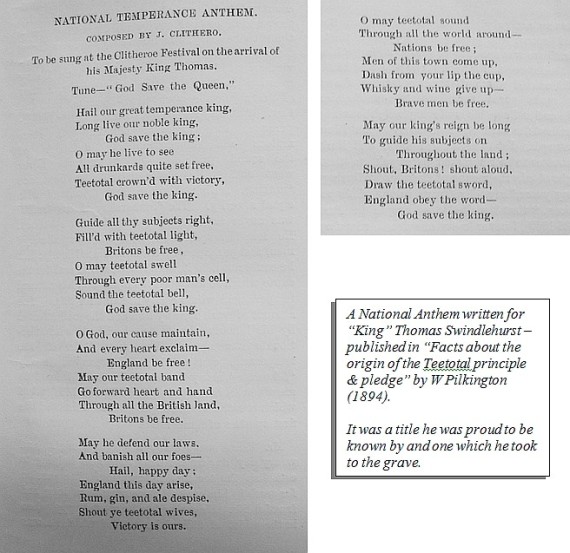

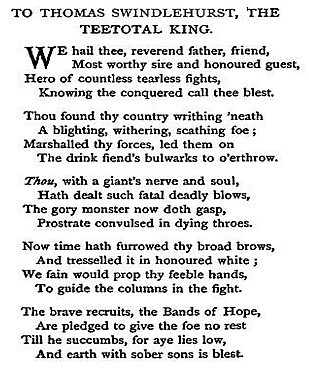

In 1836 Thomas was publicly crowned at a mock-coronation staged by the Society members as the "King of the Reformed Drunkards" and thereafter jocularly referred to as “His Majesty”; he even signed his letters from the Society as “Thomas Rex”. He had, however, been known by that name for some time before this – An article in the Worcester Herald, 9 May 1835 describes him as such. It is said that Thomas himself created the title. Not only did Preston give marked evidence of its loyalty to Thomas and his “Royal” title, but other towns also honoured him under this title and this can be seen from the poem, below, written for the Clitheroe festival.

Thomas’ most famous convert to Teetotalism was John Cassell, who founded Cassell & Co publishers of educational books and periodicals. He was also a tea and coffee merchant as the vignette below shows. One day John Cassell was working at the Manchester Exchange when he was attracted to the Tabernacle, Stevenson Square, Manchester, by a course of temperance lectures which were given by Dr. Grindrod. Cassell was fully convinced of the truth and importance of the question under Dr. Grindrod's lectures but he still did not sign any pledge. A little later on, in July 1835, he attended a lecture given by Thomas Swindlehurst on Teetotalism, and afterwards he signed the pledge.

In the History of the Temperance Movement, the historian, Winskill pays the following tribute to Thomas and gives an insight, in Thomas’ own words, of the shame he felt as a result of his past drunkenness:

“Thomas Swindlehurst (the king of the Preston drunkards) was from the first one of the most ardent and devoted friends of the cause in that town. “He was a master roller-maker, and on leaving his business so often (like many others then) devoted

more time to the gratuitous service than we had any right to expect. He was a comparitively uneducated man, but an earnest, impressive speaker, and was very well accepted by the working classes, over whom he had considerable power. When fully threescore years and ten, he had much of the vivacity and vigour of early years, and made periodical visits north and south to advocate the principles." He was

one of the early missionaries. His son Randall was also a worker in the cause, and some of his other children adopted the principles.

As long as he lived he deeply lamented the fact that his own example had led to the intemperance of his eldest son (who, however, afterwards reformed). The following is a brief sketch of one of his speeches, delivered in the Preston theatre on October 3rd 1834. ‘Here stands before you the king of the reformed drunkards. I never experience so much pleasure as I do when attending temperance meetings. I regret that the Temperance Society did not start twenty years since, for had I been sober I might have offered myself as a candidate for the borough of Preston and been worth £10,000. Yes, when I earned £4 or £5 a week, had we had a Temperance Society, we should have preserved our own rights. I now thank God that I stand fast in the liberty where with temperance has made me free. In describing the course I have led in intemperance, were I to tell the whole truth, the angels which are hovering over our meeting would hide their faces beneath their wings. I have a wife and ten children living; the eldest I used to take by the hand to the public-house, and made him a drunkard like myself at the early age of 18. My second son was also a drunkard before the age of 19. This is the effect of a bad example; and how many are there in Preston who have drunken sons, even by the example of moderate drinking. My eldest son is now a teetotaller, and I have another fellow sitting there (pointing to a boy on the stage, his son William) who goes up and down preaching temperance. The queen (alluding to his wife) would have been here but for indisposition, and I hope she will come tomorrow night. My fellow working men, do give over that nasty jerry, come and join our society, and you will be really happy.’

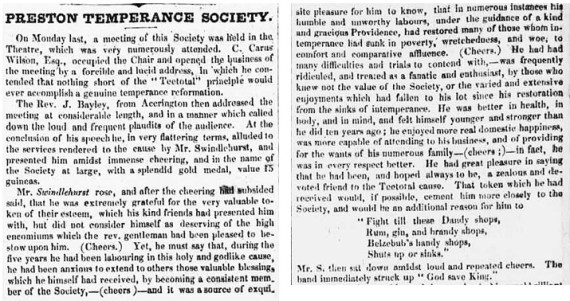

At one of the largest and most enthusiastic meetings ever held in the theatre, Preston, viz., on April [19th], 1837, Mr. Swindlehurst was presented with a gold medal, bearing the following inscription: Presented to Thomas Swindlehurst by his numerous friends in Preston, as a token of respect for his indefatigable services in promoting the cause of total abstinence from all intoxicating liquors." … Thomas Swindlehurst remained an earnest and faithful friend of the cause.

Winskill gives the correct date of the event in the Theatre Royal, however this was not reported in the Preston Chronicle until 24th June 1837 which put the event incorrectly as 19th June of that year.

When Thomas Swindlehurst Jnr. spoke about this event, several decades later, his words are as true today as they were then, “ The present generation have no idea of the life and fire of those classic times. The occasion was the recognition of my father’s position as a leader in the temperance reformation – of his exraordinary zeal, his unwearied and disinterested labours, his dauntless courage, his indefatigable and widespread services, his great success, his matchless championship in the cause – for he was in these respects a giant in those days. I think that justice has yet to be done to him.”

In the Blackburn Standard of 31st October 1838 the dissolution of the partnership between John Finch senior and Thomas Swindlehurst is announced.

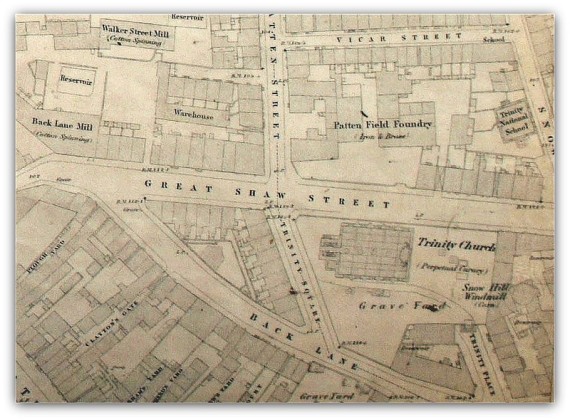

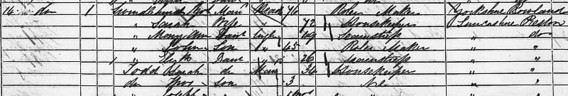

In the 1841 Census Thomas and his family are shown as living at Great Shaw Street in Preston, and at 12 Great Shaw Street in the 1851 Census.

On Saturday 5th April, 1845 the Lancaster Gazette carried an interesting article that involved Thomas. It said, under the Heading, “Escape From The Preston Lock-up - A Youth, 17 years of age, named Michael Costello, who had been apprehended on Monday on a charge of stealing a currant loaf, some sugar, and other articles, from the house of Mr Swindlehurst, Great Shaw Street, and taken to the police station, contrived to make his escape on Tuesday morning, during the time that one of the officers was sweeping and cleaning out one of the upper rooms.” The article then goes on to describe the route taken by the youth to make his escape. It also says that in his haste to escape he left behind his shoes. It also said that his apprehension was confidently anticipated as he was well known to both the borough and county police, having been convicted twice before.

Thomas’ determination not to partake of any alcohol, even for medicinal purposes is shown in an article in the Preston Chronicle of 16 May 1846. During a speech at the

Temperance Festival of that year, he spoke of a time when he had been troubled by rheumatics down his right side, “but he was determined to try the ‘cold water cure,’ so at night he got some clean

towels and soaked them in pure spring water and wrapped them round his right leg and laid them to his right side, got a dry shhet and twisted and spread it over the moist towels, got into bed and

‘slept like a top,’ and the next morning he ailed nothing; for he was able to take the stick out of the nook, hang it up in the lobby, put on his hat and march out of his house with all the pleasure

of a King - (applause). On that occasion, one doctor had recommended him to take a white-wine possett, but he thought he would try the plan which teetotallers generally thought best, and it had so

well succeeded, that he had never felt the pain since. The same doctor was afterwards troubled with the like complaint, so in return he advised the doctor to make trial of the same thing, as he was

sure it would succeed.”

It was at this same Temperance Festival that Thomas made the claim that “he was the first that advocated total abstinance, and that circumstance took place within the

walls of that Hall, [Theatre Royal], and on the right side of the chair.” This was not the first time, or the last that Thomas publicly pronounced himself the first advocate of teetotalism. In a

letter to the editor of the Preston Chronicle, published on 30 May 1868, Joseph Dearden wrote that in July 1836, at the conference of the British Temperance Association, held at Preston, and at the

World’s Temperance Convention in London in August 1846, Thomas made the same claim and on no occasion did anyone dispute it.

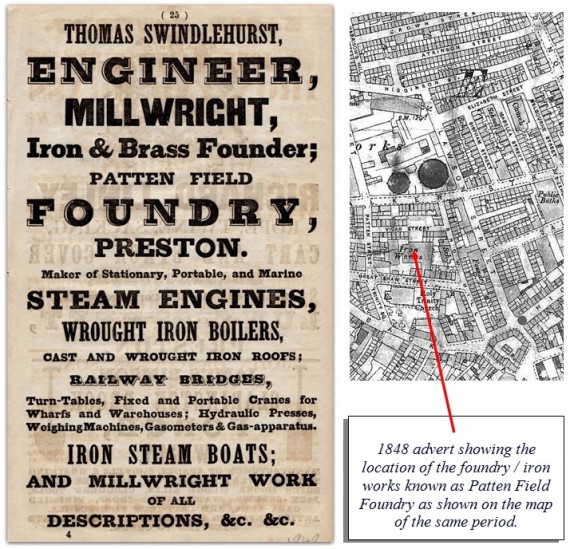

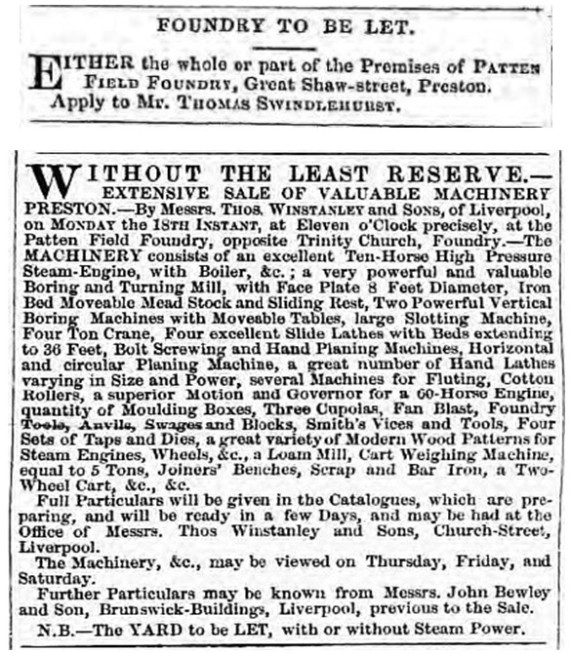

On 2 August 1851 an advertisement appeared in the Preston Chronicle showing that the Patten Field Foundry was to let. It was followed by another advertisement in the Leeds Intelligencer on the 16 August for the sale of the equipment used in the foundry. The advert provides a fascinating inventory of all the large machinery and tools that had been in use in the foundry.

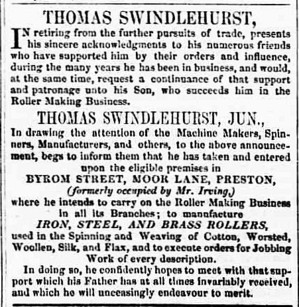

The reason for all this became clear when, in the Preston Chronicle of 20th September 1851, Thomas Swindlehurst announced his retirement from theRoller Making business and at the same time made the announcement that his son Thomas junior will take over the business from the new location of Byrom (sic.) Street, off Moor Lane. Further details of Thomas junior’s business follow later in this document.

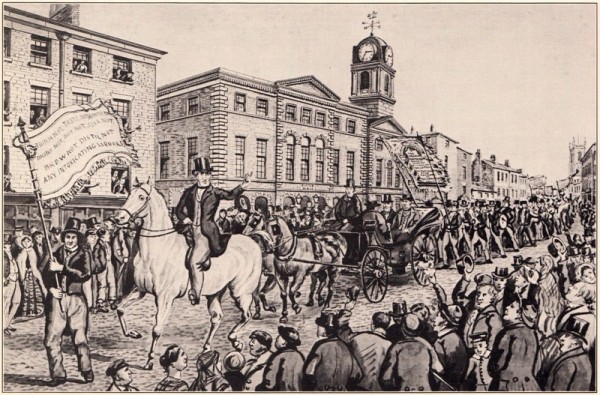

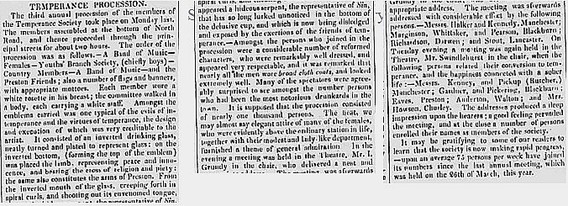

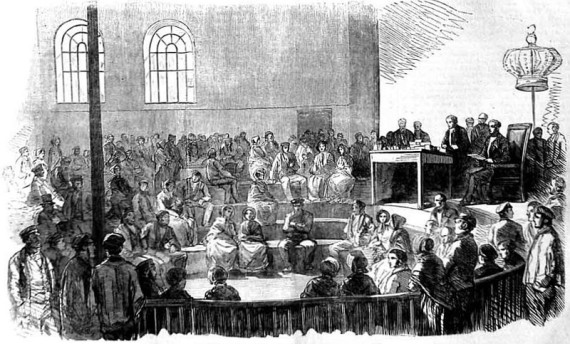

Events in 1853 – 4, in the cotton mills of Preston, inadvertently led to an artefact associated with Thomas Swindlehurst being recorded in a historical picture. Few of the thousands of readers who saw the picture at the time, and have seen it since, would have understood what it was or its significance. Between October 1853 and May 1854, 20,000 mill workers were locked out of the cotton mills of Preston in a dispute over wage cuts. The Preston Lock-Out was the longest and most expensive industrial conflict in the history of Preston. Cotton workers in Lancashire demanded that the 10-20% cut from their wages during the depression in the 1840s was restored.The town supported the workers, with a weekly collection made from working people, shopkeepers and the general public. On Mondays the striking workers received their relief payments at a gathering at the Cockpit or “Temperance Hall”.

A depiction of the Cockpit during the strike, showing the distribution of these payments, appeared in the Illustrated London News on November 12, 1853. The picture has come to be known from its title in the newspaper, “Payment of the Operatives”, and its fame is increased by the fact that Charles Dickens visited one of these meetings when he visited Preston during his research for his book “Hard Times”.

The artefact referred to is the very large regal crown that can clearly be seen behind the chairman. In a letter to the Preston Chronicle of 10 February 1883 the writer, who called himself “Justice To All”, explains that the crown had been made for a public Temperance Procession through the town a few months earlier. “The friends of the late T. Swindlehurst prevailed upon him, much against his wish, to ride upon a horse, as did also two of his sons, and several other gentlemen. The large crown, already referred to, and made especially for the occasion, was carried over Mr Swindlehurst’s head as the “King of the Teetotallers”.

On 5th July 1856 the new Temperance Hall in Preston was opened, providing an improved meeting venue to the old Cock Pit. In an 1857 Trade Directory of Preston, Thomas is listed as:

“Swindlehurst, Thomas, Teetotal King, Temperance Hall, North Road”

Having made his fortune again in partnership with John Finch, he then spent most of it in his continuing advocacy of Teetotalism. In his latter years, the following appeal was made by the Society in the Bristol Temperance Herald on 1st April 1856:

“MR. THOMAS SWINDLEHURST OF PRESTON. An appeal is being made to the teetotallers of the United Kingdom, on behalf of Mr. Thos. Swindlehurst, who is well known throughout the country as one of the earliest and most courageous champions of our cause. The documents relating to the case have been forwarded to us so late in the month that we are only able now to state that Mr. Swindlehurst, although once placed in more fortunate circumstances, and with ample means, after having travelled thousands of miles and incurred proportionate expenses to serve societies, finds himself in his old age in comparative penury. An effort is now made to purchase an annuity sufficient to maintain him in comfortable and respectable circumstances. We trust that prompt aid will be given to this benevolent undertaking. Subscriptions may be forwarded to Mr. Livesey, Bank Parade, Preston.”

The subscription was made, but it was a very spasmodic effort and the weekly allowance was short lived and amounted to a total of only £148. His last years were spent in poverty.

In the census of 1861, Thomas is living with his wife, four of his grown children and two grandchildren, at 14 St Paul’s Square, Preston.

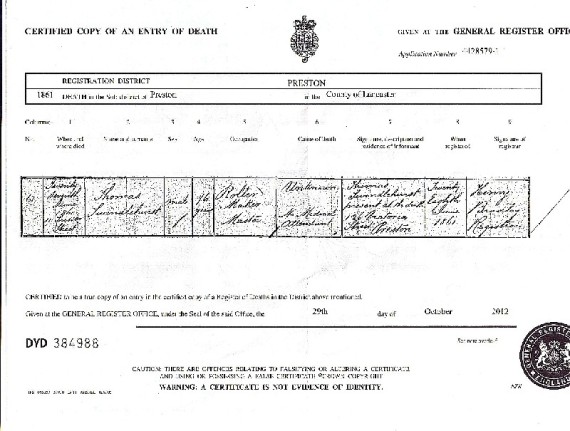

Thomas died on 27th June 1861 at the age 77 at his home, which at the time was 11 Sussex Street. His death certificate states the cause of death as Unknown – no medical attendant.

In the “History of the Temperance Movement in Great Britain and Ireland”, Samuel Couling gives a short account of Thomas’ life and of his funeral:

“He was one of the men of Preston who first signed the revised pledge of total abstinence; and although questions have been raised in relation to the birthplace of teetotalism, Thomas Swindlehurst was undoubtedly the first reclaimed character, and for many years was extensively known as the king of the reclaimed drunkards, and notwithstanding that he had to encounter every kind of opposition, contempt, and ridicule, he held on faithful to the end. As an active worker in the movement, our friend had few equals. The cause by which he had been delivered from the curse of intemperance had peculiar claims upon him, and we are happy to state that those claims were never disregarded. By night and by day, at-home and abroad, in season and out of season, in honour and in dishonour, Thomas Swindlehurst worked hard, worked long, worked efficiently, and worked successfully. During the very last week of his life he addressed several meetings at Bolton with his accustomed energy and zeal; but his work was done, his death very sudden, and his remains were carried to the grave on the 30th of June, followed by some three hundred of the temperance friends of Preston, while thousands of spectators witnessed the solemn procession. The funeral service was performed by the Rev. R. Slate, and the mournful event was improved in the temperance hall at night, Mr. Joseph Livesey presiding, and addresses were delivered by several of the early coadjutors of the departed.”

The family grave headstone in Preston Cemetery bears the following inscription:

In memory of Thomas Swindlehurst Roller Maker and ironfounder of this town, who departed this life June 27th 1861 in the 76th year of his age. An abstainer from intoxicating liquors, for some time previous to the formation of the Preston Temperance Society. He was one of the first, (If not the first) of the ‘Preston Men' to publicly advocate teetotalism as the only true principle of sobriety, and for 30 years in all parts of the United Kingdom, he devoted his time, talents and means to the spread of the Temperance cause.

Also Sarah relict of the above who departed this life February 25th 1873 aged 85 years.

Also John, son of the above, who died November 9th 1876 aged 58 years.

Also Mary Ann Swindlehurst daughter of the above who died Dec 3rd 1884 aged 73 years.