News

Home page online

This web site is a work in progress and being regularly updated. Please check back frequently to view new and updated pages.

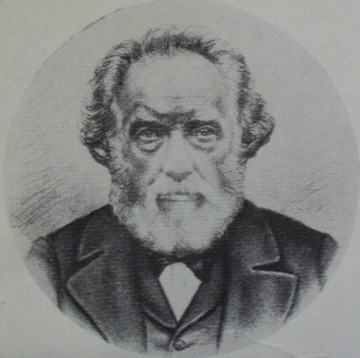

John Finch (1784 - 1857)

John Finch is largely forgotten today yet his work in Liverpool during the mid-nineteenth century, as well as nationally, although it ended usually in failure shows him as a visionary for much of what he attempted to start took root shortly after his death. Born to a poor but respectable working class family in Dudley, he received a basic education at a charity school. From there and through several clerical jobs he became a self-made and successful businessman after entering the employ of Irvin and Sons, iron merchants of Liverpool in 1818. During the rise of the industrial revolution when iron was needed for engines, machines, railways and ships he began his own business in 1827.

Early co-operative movements in Liverpool largely dependent on Finch’s initiative, failed (although ten years after his death the Rochdale Co-operatives proved the soundness of the idea). Finch, as a Unitarian Christian, understood Christianity to mean practical action to lessen suffering, poverty and injustice. He was a fervent adherent of the Temperance movement, travelling great distances in the North and into Scotland to get people to take the pledge. Further, he wanted to understand what lay behind drunkenness, and sought its economic and social causes. Among the Liverpool docks he discovered that about 120 “Lumpers”, men who were given a certain sum to load and unload ships took to ‘subcontracting’ the jobs at a lower rate. These secondary hires were done in pubs, so in order to have a chance of getting work men had to patronise the pubs; indeed, some of the lumpers kept pubs themselves.

Finch organised the setting up of a Dockers’ co-operative. He pointed out, successfully, to employers, that erecting shelters for men overseen by “a steady person” who would keep lists and assign work would remove what Rose calls ‘the endemic dishonesty of desperation, and the shoddy work of drunkenness.’ The Dock Labourers’ Society began successfully, recruiting 2,000 of 6,000 dock and warehouse workers. Wealthy merchants and sympathisers contributed so that the fixed wage went from two shillings a day to three shillings, and the cutting out of the middle man’s take also increased income. Branch offices were equipped with libraries and school equipment, and literate dockers were to instruct their mates during slack periods.

But for many reasons, the scheme eventually failed. There was not enough work to go around. Employers were extremely suspicious of working class ‘societies’. The collapse of the society in 1831 is to be seen in the context of pressure of immigration from Wales, Scotland and Ireland: far too many seeking far too little work. Finch, looking back, became convinced that while drunkenness played a part, and was understandable given the circumstances, all hopes of social change were doomed unless this vice were attacked, and to this he devoted much of his energies. Alongside this he campaigned for a national education system – one which would see young children schooled in boarding institutions at the edge of the city, away from the dreadful conditions in which they had to grow. He also argued for clearance of slums and a municipal house building programme. Regarding unemployment he called on ‘gentlemen and ladies’ to provide jobs which would be part of workers’s production co-operatives.

Finch was a devotee of Robert Owen and his ideas, something we’ll look at in a later post, but here it can be said that the core values of what would be a strand of English socialism were evident in Liverpool.

Finch, a merchant and never questioning the basic structures of economics and society, was an advocate of this form of socialism. He devoted a great deal of time and energy to the building of the Liverpool Hall of Science in Lord Nelson Street. This was one of several built by ‘The Universal Community Society of Rational Religionists’ throughout the country, the largest and most expensive. Yet it seems not to have been used for political meetings, soon after its completion being abandoned by the socialists.

Finch moved from dealing in iron to owning a Liverpool iron foundry. His intention was that over a period of time it would become a workers’ co-operative, run by, worked by workers with substantial investment in the enterprise. Tis project failed for various reasons – most notably an engineers’ strike. Finch’s work with Robert Owen also ended in failure.

Some questions are raised. How much of history – especially as here, the history of Liverpool and its working classes – hidden from standard accounts? Would Finch, of the merchant class himself despite his working class origins, be fairly described as a socialist? Was Finch a radical or a reformer, or a radical reformer perhaps? What is radicalism?

The story will be picked up again later with an unusual connection. Finch, although a committed Christian was branded an atheist by many and expelled from the Temperance movement. The Bishop of Liverpool’s work on behalf of the poor and labouring classes in the twentieth century was called ‘Marxist’ by some. It may be that part of the history of reform or radical reform or raised voices in the name of justice always bring about condemnation from some quarters, and this too is part of on-going history.

The above is based on an essay by:

Professor R.B. Rose - John Finch, 1784-1857; a Liverpool Disciple of Robert Owen - (1958) first appeared in the Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire