News

Home page online

This web site is a work in progress and being regularly updated. Please check back frequently to view new and updated pages.

5. The River Dee & The Latchcraft Pits

If one event was to be singled out as the most important in the development of Shotton, it must be the cutting of a navigable channel in the River Dee. Until this event, the area to the east of the present main road formed part of the high tide flood plain. Low tide revealed marshlands covered with green sward.

As early as Roman times, the River was an important means of transport. In the 1st century A.D. Roman merchant ships would have been seen sailing along the Dee, importing wood and Welsh slate for the building of the DEVA fortress, and exporting sandstone from the Chester area for the defences of SEGONTIVM (Caernarfon).

During the 11th to the 16th centuries, Chester was a busy and thriving sea port, one of the largest in England. However, during the 17th century, erosion of the estuary

shore caused serious silting of the river. Its effect was noted as early as 1405, but it was not until 1677 that the first navigational improvement scheme was proposed. In this year Andrew Jarrington

suggested building a canal from Chester to Flint. Hearing of these proposals, a man by the name of John Sparrow, in the same year, set up the Latchcraft Colliery. It was located just south of the

16th century workings in the Old Banks area. The proximity of the improved river would have been ideal for Sparrow to transport his coal to Chester. Unfortunately for him, the project was shelved,

causing serious problems for the colliery. It is believed that the coal was transported from the pits in carts, down the lower end of Killins Lane and Nine Houses Lane (Brook Road). The coal would

then have been loaded onto barges at the Wepre Gutter at low tide, where they would wait until a high tide to be floated out to the river. This difficulty in transportation was probably the reason

for the failure of the colliery. It closed after only a few years of operation.

The name Latchcraft, or Latchcroft is still a popular house name in Shotton, but its origin is uncertain. It may be derived from the old English words meaning "a boggy

stream," perhaps referring to the Wepre Brook. However, a man of some wealth, Richard Lache, lived in Hawarden in 1569. It is possible that he owned the land at this time.

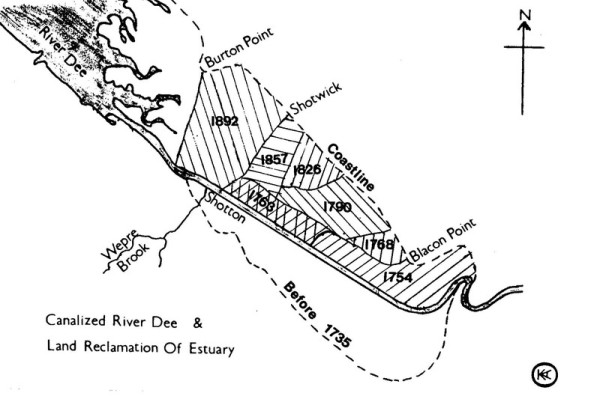

Further suggestions for canalising the River Dee were proposed in subsequent years, but the scheme which finally won approval was the proposal by Nathaniel Kinderley in

1732. Between 1735 - 6 Nathaniel Kinderley & Company cut a new channel on the Welsh side of the existing river from Chester to Golftyn. The new Dee channel was opened to shipping in 1737. In 1740

Kinderley's company became known as the River Dee Company. It seems that they neglected their duty to maintain the channel, allowing it to silt up again. Instead they turned their attention to the

thousands of acres of reclaimed marshlands around Sealand and Saltney which, by the year 1861 was raising £8000 in annual rent.

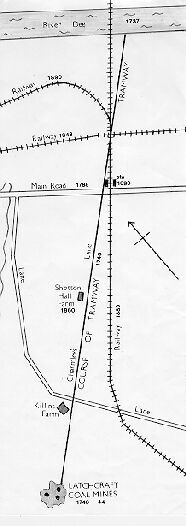

One of the first industries to arrive in Shotton occurred in 1740 when a Chester company opened up new shafts in the Latchcraft coalfields. On this occasion, the pits were situated about 250 metres southwest of Killins Farm. Gorse covered spoil heaps from the workings are still visible to this day, and stand to a height of 35 feet. This gives a indication that the mines were worked for about four years. A large brick building associated with the workings was still standing in a field south of the workings in 1895. The company constructed a horse drawn wooden tramway from the pits to the river, near to where the Hawarden Bridge now stands. From here the coal was transported to Chester. This tramway is believed to have been one of the first of its kind in Britain. In later years, after the track had been removed, the northern end, between the railway station and the river, was obliterated by the railway embankment. At the southern end its course came to be used as a footpath, eventually to be known as Charmley's Lane. About half of this lane now lies under the Pippins and Brambles housing estate, but the southern half still exists as a reminder of a long-gone industry.

Walking along this quiet lane today, alongside the playing fields, it is difficult to imagine the bustling industry that took place there 250 years ago.